Dermatofibromas (also known as histiocytomas) are common benign fibrous skin lesions. They are caused by the abnormal growth of dermal dendritic histiocyte cells often following a precipitating injury. Common areas include the arms and legs and occurs more often in women.

Etiology: Traditionally, dermatofibromas were attributed to a reaction to trauma such as insect bites. However, the precise aetiology is unclear. Some believe them to be benign neoplasms rather than reactive in origin.

Pathology: The most common dermatofibromas contain a mixture of fibroblasts, macrophages and blood vessels. Most involve the dermis and may extend to the subcutis. A number of less common variants where the histology differs ,such as the aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma, hemosiderotic fibrous histiocytoma, cellular fibrous histiocytoma and epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma, have been described. Different types are associated with different behaviours and outcomes.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Dermatofibromas are most often found on the arms and legs of women. They are small brown or reddish-brown mobile nodules, and they feel quite firm. They may be tender to touch. Many lesions demonstrate a "dimple sign," where the central portion puckers as the lesion is compressed on the sides. They generally do not change in size.

Study and Memorize Medical Conditions With The Help Of Photos. Useful Site For Medical Students, Doctors And Nurses.

Pages

▼

Wednesday, May 31, 2017

Tuesday, May 30, 2017

A Skin lesion that developed Over A 4 week period....

The pictured skin lesion developed over a 4-week period. The most likely diagnosis is

A) Melanoma

B) Basal cell carcinoma

C) Keratoacanthoma

D) Dermatofibroma

E) Molluscum contagiosum

Answer:

A) Melanoma

B) Basal cell carcinoma

C) Keratoacanthoma

D) Dermatofibroma

E) Molluscum contagiosum

Answer:

Monday, May 29, 2017

A 45 years old patient presents with history of cough and expectoration for several months....

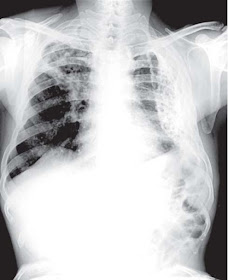

A 45 years old patient presents with history of cough and expectoration for several months. His chest X ray is shown below:

Describe the findings on the X ray and what could be the diagnosis?

Radiological Findings And Explanation

X-ray chest shows that the lungs are large in volume with streaky shadows and multiple cystic lesions with air fluid levels. These cystic lesions can also be seen through the heart shadow. This is most probably a case of bronchiectasis.

Describe the findings on the X ray and what could be the diagnosis?

Radiological Findings And Explanation

X-ray chest shows that the lungs are large in volume with streaky shadows and multiple cystic lesions with air fluid levels. These cystic lesions can also be seen through the heart shadow. This is most probably a case of bronchiectasis.

Saturday, May 27, 2017

Left Ventricular Aneurysm.- ECG

The ECG shown below was obtained in an asymptomatic patient with a history of myocardial infarction about 2 years ago.

(click to enlarge)

ECG Findings

• ST elevation in anterior contiguous leads

• Deep pathologic Q waves in anterior leads

Clinical Pearls

1. ST segment elevation which occurs in the setting of a myocardial infarction should resolve within days under normal circumstances.

2. Persistent ST-segment elevation occurring for weeks or longer after a myocardial infarction is suspicious for ventricular aneurysm.

3. Ventricular aneurysms may follow a large myocardial infarction in the anterior portion of the heart.

4. The aneurysm consists of scarred myocardium, which does not contract but bulges outward during systole; complications include congestive heart failure, myocardial

rupture, arrhythmias, and thrombus formation.

(click to enlarge)

ECG Findings

• ST elevation in anterior contiguous leads

• Deep pathologic Q waves in anterior leads

Clinical Pearls

1. ST segment elevation which occurs in the setting of a myocardial infarction should resolve within days under normal circumstances.

2. Persistent ST-segment elevation occurring for weeks or longer after a myocardial infarction is suspicious for ventricular aneurysm.

3. Ventricular aneurysms may follow a large myocardial infarction in the anterior portion of the heart.

4. The aneurysm consists of scarred myocardium, which does not contract but bulges outward during systole; complications include congestive heart failure, myocardial

rupture, arrhythmias, and thrombus formation.

Wednesday, May 24, 2017

Introduction to Folliculitis, furuncles, and carbuncles

Folliculitis: A bacterial infection of the hair follicle, folliculitis causes the formation of a pustule of the hair follicle opening. The infection can be superficial (follicular impetigo or Bockhart’s impetigo) or deep (sycosis barbae).

Furuncles, commonly known as boils, are another form of deep folliculitis.

Carbuncles are a group of interconnected furuncles.

The prognosis depends on the severity of the infection and the patient’s physical condition and ability to resist infection.

Causes

The most common cause of folliculitis, furuncles, or carbuncles is coagulasepositive Staphylococcus aureus.

Causes

The most common cause of folliculitis, furuncles, or carbuncles is coagulasepositive Staphylococcus aureus.

Predisposing factors include

- an infected wound,

- moisture,

- obesity,

- diabetes mellitus,

- skin disease,

- poor hygiene,

- debilitation,

- tight clothes,

- friction, and

- immunosuppressive therapy.

Signs and symptoms

Folliculitis, furuncles, and carbuncles have different signs and symptoms.

Folliculitis, furuncles, and carbuncles have different signs and symptoms.

Monday, May 22, 2017

Description Of Exudates As Seen On Fundoscopy

Hard exudates are refractile, yellowish deposits with sharp margins composed of fat-laden macrophages and serum lipids.

Occasionally the lipid deposits form a partial or complete ring (called a circinate ring) around the leaking area of pathology. If the lipid leakage is located near the fovea, a spoke or star-type distribution of the hard exudates may be seen.

Hard Exudates. Linear collection of yellow lipid deposits with sharp margins in macula.

Cotton wool spots, or soft “exudates,” are actually microinfarctions of the retinal nerve fiber layer, and appear white with soft or fuzzy edges.

Cotton Wool Spots. White lesions with fuzzy margins, seen here approximately one-fifth to one-fourth disk diameter in size. Orientation of cotton wool spots generally follows the curvilinear

arrangement of the nerve fiber layer. Intraretinal hemorrhages and intraretinal vascular abnormalities are also present.

Inflammatory exudates are secondary to retinal or chorioretinal inflammation.

Occasionally the lipid deposits form a partial or complete ring (called a circinate ring) around the leaking area of pathology. If the lipid leakage is located near the fovea, a spoke or star-type distribution of the hard exudates may be seen.

Hard Exudates. Linear collection of yellow lipid deposits with sharp margins in macula.

Cotton wool spots, or soft “exudates,” are actually microinfarctions of the retinal nerve fiber layer, and appear white with soft or fuzzy edges.

Cotton Wool Spots. White lesions with fuzzy margins, seen here approximately one-fifth to one-fourth disk diameter in size. Orientation of cotton wool spots generally follows the curvilinear

arrangement of the nerve fiber layer. Intraretinal hemorrhages and intraretinal vascular abnormalities are also present.

Inflammatory exudates are secondary to retinal or chorioretinal inflammation.

Introduction to Kaposi’s sarcoma

Kaposi’s sarcoma, a cancer of the lymphatic cell wall, affects tissues under the skin or mucous membranes that line the mouth, nose, and anus. In recent years, the incidence of Kaposi’s sarcoma has risen dramatically along with the incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. It’s now the most common HIV-related cancer.

Kaposi’s sarcoma causes structural and functional damage. It progresses aggressively, involving the lymph nodes, the viscera and, possibly, GI structures.

Kaposi’s sarcoma causes structural and functional damage. It progresses aggressively, involving the lymph nodes, the viscera and, possibly, GI structures.

Etiology

The exact cause of Kaposi’s sarcoma is unknown, but the disease may be related to immunosuppression. Genetic or hereditary predisposition is also suspected.

Signs and symptoms

The exact cause of Kaposi’s sarcoma is unknown, but the disease may be related to immunosuppression. Genetic or hereditary predisposition is also suspected.

Signs and symptoms

The initial sign of Kaposi’s sarcoma is one or more obvious lesions in various shapes, sizes, and colors (ranging from red-brown to dark purple) that appear most commonly on the skin, buccal mucosa, hard and soft palates, lips, gums, tongue, tonsils, conjunctivae, and sclerae.

With advanced disease, the lesions may join, becoming one large plaque. Untreated lesions may appear as large, ulcerative masses.

With advanced disease, the lesions may join, becoming one large plaque. Untreated lesions may appear as large, ulcerative masses.

Kaposi's Sarcoma Seen as a tumor on the roof of the mouth

Kaposi Sarcoma Affecting the skin

Other signs and symptoms include:

Other signs and symptoms include:

- a history of HIV infection

- pain (if the sarcoma advances beyond the early stages or if a lesion breaks down or impinges on nerves or organs)

- edema from lymphatic obstruction

- dyspnea (in cases of pulmonary involvement), wheezing, hypoventilation, and respiratory distress from bronchial blockage.

- The most common extracutaneous sites are the lungs and GI tract (esophagus, oropharynx, and epiglottis).

Sunday, May 21, 2017

Intussusception - Clinical Features And Management

Causes

Intussusception is most common in infants and is three times more common in males than in females. It typically occurs between ages 3 months and 3 years, with a peak incidence between ages 6 and 9 months.

Studies suggest that intussusception may be linked to viral infections because seasonal peaks are noted—in late spring and early summer, coinciding with the peak incidence of enteritis, and in midwinter, coinciding with the peak incidence of respiratory tract infections.

The cause of most cases of intussusception in infants is unknown. In older children, polyps, alterations in intestinal motility, hemangioma, lymphosarcoma, lymphoid hyperplasia, or Meckel’s diverticulum may trigger the process. In adults, intussusception usually results from benign or malignant tumors (65% of patients). It may also result from polyps, Meckel’s diverticulum, gastroenterostomy with herniation, or an appendiceal stump. In the elderly, decreased GI elasticity and motility can lead to intussusception.

Pathology

When a bowel segment (the intussusceptum) invaginates, peristalsis propels it along the bowel, pulling more bowel along with it; the receiving segment is the intussuscipiens. This invagination produces edema, hemorrhage from venous engorgement, incarceration, and obstruction. If treatment is delayed for longer than 24 hours, strangulation of the intestine usually occurs, with gangrene, shock, and perforation.

Sixth Nerve (Abducens Nerve) Palsy

The abducens nerve (Cranial Nerve VI) innervates the lateral rectus muscle and is the most common single muscle palsy, causing loss of abduction and resultant horizontal diplopia, worse in ipsilateral

gaze. Associated findings are dependent on the location of the lesion.

Etiology: Within the pons, involvement of the corticospinal tract results in contralateral hemiparesis. The abducens has the longest intracranial course of any nerve, and therefore is vulnerable to stretching or compression secondary to elevated intracranial pressure, trauma, neurosurgical manipulation, and cervical traction.

Also, any meningeal process (infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic) can affect this portion of the sixth nerve.

Aneurysmal compression is uncommon.

Prior to entering the cavernous sinus, the nerve crosses the petrous portion of the temporal bone. Trauma with temporal bone fracture can result in a combination of sixth- and seventh-nerve palsies.

Cavernous sinus pathology is suggested by the involvement of the internal carotid artery, venous drainage of the eye and orbit, trochlear and oculomotor nerves, the first division of the trigeminal nerve, and the ocular sympathetics.

Microvascular changes secondary to diabetes, hypertension, and giant cell arteritis can compromise

function.

Sixth-Nerve Palsy. Loss of abduction of the left eye is seen in lateral gaze.

Management:

Associated signs and symptoms guide the workup.

gaze. Associated findings are dependent on the location of the lesion.

Etiology: Within the pons, involvement of the corticospinal tract results in contralateral hemiparesis. The abducens has the longest intracranial course of any nerve, and therefore is vulnerable to stretching or compression secondary to elevated intracranial pressure, trauma, neurosurgical manipulation, and cervical traction.

Also, any meningeal process (infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic) can affect this portion of the sixth nerve.

Aneurysmal compression is uncommon.

Prior to entering the cavernous sinus, the nerve crosses the petrous portion of the temporal bone. Trauma with temporal bone fracture can result in a combination of sixth- and seventh-nerve palsies.

Cavernous sinus pathology is suggested by the involvement of the internal carotid artery, venous drainage of the eye and orbit, trochlear and oculomotor nerves, the first division of the trigeminal nerve, and the ocular sympathetics.

Microvascular changes secondary to diabetes, hypertension, and giant cell arteritis can compromise

function.

Management:

Associated signs and symptoms guide the workup.

Thursday, May 18, 2017

Placental Abruption

A 32 year old woman G4 P3+0 presents to the emergency department with heavy bleeding and lower abdominal pain at 24 weeks gestation. On Examination there was no fetal heart beat, and the uterus was extremely tender on palpation. Ultrasound shows separation of the placenta, and a diagnosis of placental abruption was made which was managed accordingly.

Placental Abruption - Discussion

In placental abruption also kniown as abruptio placentae , the placenta separates from the uterine wall prematurely, usually after the 20th week of gestation, producing hemorrhage. Abruptio placentae is most common in multigravidas—usually in women older than age 35—and is a common cause of bleeding during the second half of pregnancy. Fetal prognosis depends on gestational age and amount of blood lost; maternal prognosis is good if hemorrhage can be controlled.

Causes

In many cases, the cause of abruptio placentae is unknown.

Causes

In many cases, the cause of abruptio placentae is unknown.

Predisposing factors include

- cocaine use,

- trauma (such as a direct blow to the uterus resulting from abuse or accidental trauma),

- placental site bleeding from a needle puncture during amniocentesis,

- chronic or pregnancy-induced hypertension (which raises pressure on the maternal side of the placenta),

- multiparity of more than five,

- short umbilical cord,

- dietary deficiency,

- smoking,

- advanced maternal age, and

- pressure on the venae cavae from an enlarged uterus.

A Newborn Baby with Difficulty Breathing since Birth

X ray of a newborn baby with difficulty breathing since birth is shown below:

Radiological Findings: X-ray chest shows opaque left hemithorax and the entire mediastinum is pulled to the left, the right lung has herniated beyond the midline. The endotracheal tube and Ryles tube are in situ.

Diagnosis suggested is complete agenesis of left lung. This can be confirmed on CT chest.

Comments:

The findings seen on chest film are absence of lung, opaque hemithorax, mediastinal shift with hernia of contralateral lung to the affected side with normal and symmetrical bony thorax.

CT chest can be helpful to differentiate the three categories of agenesis

(a) complete agenesis,

(b) lung aplasia and

(c) lung hypoplasia.

Lung agenesis is rare, developmental anomaly of the lung. It can be:

1. Complete agenesis, manifested by total agenesis of lung tissue, bronchus and pulmonary vessels.

2. Lung aplasia manifested by a rudimentary bronchus but absent lung tissue and pulmonary vessels.

3. Lung hypoplasia manifested by rudimentary bronchus with hypoplastic lung tissue and pulmonary vessels.

Wednesday, May 17, 2017

Introduction to Kyphosis

Normally, the spine displays some convexity, but excessive thoracic kyphosis is pathologic. Kyphosis occurs in children and adults.

Causes

Congenital kyphosis is rare but usually severe, with resultant cosmetic deformity and reduced pulmonary function.

Adolescent kyphosis

Also called Scheuermann’s disease, juvenile kyphosis, and vertebral epiphysitis, adolescent kyphosis is the most common form of this disorder. It may result from growth retardation or a vascular disturbance in the vertebral epiphysis (usually at the thoracic level) during periods of rapid growth or from congenital deficiency in the thickness of the vertebral plates.

Adolescent kyphosis

Also called Scheuermann’s disease, juvenile kyphosis, and vertebral epiphysitis, adolescent kyphosis is the most common form of this disorder. It may result from growth retardation or a vascular disturbance in the vertebral epiphysis (usually at the thoracic level) during periods of rapid growth or from congenital deficiency in the thickness of the vertebral plates.

Other causes include infection, inflammation, aseptic necrosis, and disk degeneration. The subsequent stress of weight bearing on the compromised vertebrae may result in the thoracic hump commonly seen in adolescents with kyphosis. Symptomatic adolescent kyphosis is more prevalent in girls than in boys and usually occurs between ages 12 and 16.

Adult kyphosis

Also known as adult roundback, adult kyphosis may result from degeneration of intervertebral disks, atrophy, or osteoporotic collapse of the vertebrae that’s associated with aging; from an endocrine disorder, such as hyperparathyroidism or Cushing’s disease; or from prolonged steroid therapy.

Adult kyphosis may also result from conditions such as arthritis, Paget’s disease, polio, compression fracture of the thoracic vertebrae, metastatic tumor, plasma cell myeloma, or tuberculosis.

Adult kyphosis

Also known as adult roundback, adult kyphosis may result from degeneration of intervertebral disks, atrophy, or osteoporotic collapse of the vertebrae that’s associated with aging; from an endocrine disorder, such as hyperparathyroidism or Cushing’s disease; or from prolonged steroid therapy.

Adult kyphosis may also result from conditions such as arthritis, Paget’s disease, polio, compression fracture of the thoracic vertebrae, metastatic tumor, plasma cell myeloma, or tuberculosis.

Horner Syndrome - Clinical Features And Management

Horner syndrome (miosis, ptosis, and anhidrosis) is secondary to loss of ocular sympathetic innervation.

- Ptosis is less than 2 mm, the result of paralysis of Müller muscle, innervated by the sympathetic pathway.

- Anhidrosis is often not apparent to patients or clinicians.

- A pupillary finding specific in Horner syndrome is dilation lag. Because the dilator muscle is weak,

- the pupil dilates more slowly than the normal pupil.

This loss of ocular sympathetic innervation can be produced by a lesion anywhere along a three-neuron sympathetic pathway, from the hypothalamus down through the brain stem to the cervical cord, in the apex of the chest, along the carotid sheath, and in the cavernous sinus or orbit.

Isolated Horner syndrome presenting with head or neck pain suggests an internal carotid artery dissection.

Management

Associated signs and symptoms help direct the workup. A patient with cranial nerve abnormalities requires CT or MRI imaging and admission. In the setting of cervical spine trauma, neck immobilization and appropriate imaging studies are instituted. Consider carotid artery dissection in neck pain without trauma.

Tuesday, May 16, 2017

Cerebral 'T waves' on ECG

ECG Findings

• Inverted, wide T waves are most notable in precordial leads (can be seen in any lead).

• QT interval prolongation.

Cerebral T Waves. This ECG was obtained on a patient with a severe acute hemorrhagic CVA

(click on image to enlarge)

Clinical Points To Remember:

1. These are associated with acute cerebral disease, most notably an ischemic cerebrovascular event or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

2. They may be accompanied by ST segment changes, U waves, and/or any rhythm abnormality.

3. Differential diagnosis includes extensive myocardial ischemia.

• Inverted, wide T waves are most notable in precordial leads (can be seen in any lead).

• QT interval prolongation.

Cerebral T Waves. This ECG was obtained on a patient with a severe acute hemorrhagic CVA

(click on image to enlarge)

Clinical Points To Remember:

1. These are associated with acute cerebral disease, most notably an ischemic cerebrovascular event or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

2. They may be accompanied by ST segment changes, U waves, and/or any rhythm abnormality.

3. Differential diagnosis includes extensive myocardial ischemia.

Monday, May 15, 2017

Sunday, May 14, 2017

Allergic Purpura - Clinical features And Management

When allergic purpura primarily affects the GI tract with accompanying joint pain, it’s called Henoch-Schönlein syndrome or anaphylactoid purpura. However, the term allergic purpura applies to purpura associated with many other conditions, such as erythema nodosum. An acute attack of allergic purpura can last for several weeks and is potentially fatal (usually from renal failure); however, most patients do recover.

Fully developed allergic purpura is persistent and debilitating, possibly leading to chronic glomerulonephritis (especially following a streptococcal infection). Allergic purpura affects more males than females and is most prevalent in children ages 3 to 7. The prognosis is more favorable for children than for adults.

Causes

The most common identifiable cause of allergic purpura is probably an autoimmune reaction directed against vascular walls, triggered by a bacterial infection (particularly streptococcal infection). Typically, an upper respiratory tract infection occurs 1 to 3 weeks before the onset of symptoms. Other possible causes include allergic reactions to some drugs and vaccines, allergic reactions to insect bites, and allergic reactions to some foods (such as wheat, eggs, milk, and chocolate).

Fully developed allergic purpura is persistent and debilitating, possibly leading to chronic glomerulonephritis (especially following a streptococcal infection). Allergic purpura affects more males than females and is most prevalent in children ages 3 to 7. The prognosis is more favorable for children than for adults.

Causes

The most common identifiable cause of allergic purpura is probably an autoimmune reaction directed against vascular walls, triggered by a bacterial infection (particularly streptococcal infection). Typically, an upper respiratory tract infection occurs 1 to 3 weeks before the onset of symptoms. Other possible causes include allergic reactions to some drugs and vaccines, allergic reactions to insect bites, and allergic reactions to some foods (such as wheat, eggs, milk, and chocolate).

Clinical Features

Allergic purpura is characterized by purple skin lesions that are macular, ecchymotic, and varying in size, usually appearing in symmetrical patterns on the arms and legs. The lesions are caused by vascular leakage into the skin and mucous membranes and are accompanied by pruritus, paresthesia and, occasionally, angioneurotic edema. In children, the lesions are generally urticarial, and they usually expand and become hemorrhagic. Scattered petechiae may appear on the legs, buttocks, and perineum.

Allergic purpura is characterized by purple skin lesions that are macular, ecchymotic, and varying in size, usually appearing in symmetrical patterns on the arms and legs. The lesions are caused by vascular leakage into the skin and mucous membranes and are accompanied by pruritus, paresthesia and, occasionally, angioneurotic edema. In children, the lesions are generally urticarial, and they usually expand and become hemorrhagic. Scattered petechiae may appear on the legs, buttocks, and perineum.

Corneal Ulcer - Clinical features And Management

A corneal ulcer is an inflammatory and ulcerative keratitis.

Common infectious etiologies include

- Bacterial corneal ulcers are commonly associated with extended-wear contact lenses.

- Fungal infections may also arise from trauma involving vegetable matter such as a tree branch. - - - -Acanthamoeba infections may also occur from swimming in lakes, especially while wearing contact lenses.

Corneal Ulcer. A small circular corneal infiltrate is seen adjacent to the white flash photography reflection. Diffuse conjunctival hyperemia with a nasal ciliary flush is seen.

Clinical Features:Patients present with pain, photophobia, decreased vision, discharge, and a foreign body sensation.

Ocular findings include a corneal infiltrate, typically a round white spot, with conjunctival hyperemia, meiosis, and chemosis.

Slitlamp biomicroscopy may demonstrate an epithelial defect with fluorescein uptake. Anterior chamber findings can include cells and flare, keratic precipitates, and a hypopyon.

Common infectious etiologies include

- bacteria (Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Pseudomonas) and

- viruses (herpes simplex, adenovirus).

- Rare causes of corneal ulcers include fungal infections and Acanthamoeba, a ubiquitous protozoan associated with contaminated contact lens solutions.

- Bacterial corneal ulcers are commonly associated with extended-wear contact lenses.

- Fungal infections may also arise from trauma involving vegetable matter such as a tree branch. - - - -Acanthamoeba infections may also occur from swimming in lakes, especially while wearing contact lenses.

Corneal Ulcer. A small circular corneal infiltrate is seen adjacent to the white flash photography reflection. Diffuse conjunctival hyperemia with a nasal ciliary flush is seen.

Clinical Features:Patients present with pain, photophobia, decreased vision, discharge, and a foreign body sensation.

Ocular findings include a corneal infiltrate, typically a round white spot, with conjunctival hyperemia, meiosis, and chemosis.

Slitlamp biomicroscopy may demonstrate an epithelial defect with fluorescein uptake. Anterior chamber findings can include cells and flare, keratic precipitates, and a hypopyon.

Fracture of Nose

The most common facial fracture, a fractured nose usually results from blunt injury and is commonly associated with other facial fractures. The severity of the fracture depends on the direction, force, and type of the blow.

A severe, comminuted fracture may cause extreme swelling or bleeding that may jeopardize the airway and require tracheotomy during early treatment. Inadequate or delayed treatment may cause permanent nasal displacement, septal deviation, and obstruction.

Causes

With low-energy injuries, noncomminuted nasal bone fragments are caused by low-velocity trauma. Such injuries could occur in the following situations:

Immediately after the injury, a nosebleed may occur, and soft-tissue swelling may quickly obscure the break. After several hours, pain, periorbital ecchymoses, and nasal displacement and deformity are prominent. A possible complication is septal hematoma, which may lead to abscess formation, resulting in vascular septic necrosis and saddle nose deformity.

A severe, comminuted fracture may cause extreme swelling or bleeding that may jeopardize the airway and require tracheotomy during early treatment. Inadequate or delayed treatment may cause permanent nasal displacement, septal deviation, and obstruction.

Causes

With low-energy injuries, noncomminuted nasal bone fragments are caused by low-velocity trauma. Such injuries could occur in the following situations:

- injuries created during fistfights (hand or fist blows only, no blunt instruments)

- uncomplicated falls such as tripping

- low-velocity motor vehicle collision.

- injuries sustained from a leveraged blow to the nose using an object such as a stick, pipe, or other blunt object

- falls from heights

- sport injuries with fast-moving projectiles, such as a ball or puck

- high-velocity motor vehicle collisions.

Immediately after the injury, a nosebleed may occur, and soft-tissue swelling may quickly obscure the break. After several hours, pain, periorbital ecchymoses, and nasal displacement and deformity are prominent. A possible complication is septal hematoma, which may lead to abscess formation, resulting in vascular septic necrosis and saddle nose deformity.

Saturday, May 13, 2017

Pericarditis - A Brief Discussion And Description Of ECG Changes

Pericarditis : Acute inflammation of the pericardium characteristically produces chest pain, low grade fever, and a pericardial friction rub.

Pericarditis and myocarditis commonly co-exist.

Causes

• Myocardial infarction (including Dressler’s syndrome).

• Viral (Coxsackie A9, B1-4, Echo 8, mumps, EBV, CMV, varicella, HIV, rubella, Parvo B19).

• Bacterial (pneumococcus, meningococcus, Chlamydia , gonorrhoea, Haemophilus ).

• Tuberculosis (TB; especially in patients with HIV)

• Locally invasive carcinoma (eg bronchus or breast).

• Rheumatic fever .

• Uraemia.

• Collagen vascular disease (SLE, polyarteritis nodosa, rheumatoid arthritis).

• After cardiac surgery or radiotherapy.

• Drugs (hydralazine, procainamide, methyldopa, minoxidil).

Diagnosis

Classical features of acute pericarditis are pericardial pain, a friction rub and concordant ST elevation on ECG. The characteristic combination of clinical presentation and ECG changes often results in a definite diagnosis.

Chest pain is typically sharp, central, retrosternal, and worse on deep inspiration, change in position, exercise, and swallowing.

A large pericardial effusion may cause dysphagia by compressing the oesophagus.

A pericardial friction rub is often intermittent, positional, and elusive. It tends to be louder during inspiration, and may be heard in both systole and diastole. Low grade fever is common.

Appropriate investigations include:

- ECG,

- chest X-ray,

- CBC, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR),

- C-reactive protein (CRP),

- U&E, and

- troponin.

Friday, May 12, 2017

Introduction to Laryngeal cancer

The most common form of laryngeal cancer is squamous cell carcinoma (95%); rare forms include adenocarcinoma, sarcoma, and others. Such cancer may be intrinsic or extrinsic.

An intrinsic tumor is on the true vocal cord and tends not to spread because underlying connective tissues lack lymph nodes. An extrinsic tumor is on some other part of the larynx and tends to spread early.

Gender and Age

Laryngeal cancer is nine times more common in males than in females; most victims are between ages 50 and 65.

Causes

With laryngeal cancer, major predisposing factors include

- smoking and alcoholism;

- minor factors include chronic inhalation of noxious fumes and familial tendency.

Classification

Laryngeal cancer is classified according to its location:

With intrinsic laryngeal cancer, the dominant and earliest indication is hoarseness that persists longer than 3 weeks; with extrinsic cancer, it’s a lump in the throat or pain or burning in the throat when drinking citrus juice or hot liquid. Later signs and symptoms of metastasis include dysphagia, dyspnea, cough, enlarged cervical lymph nodes, and pain radiating to the ear.

Laryngeal cancer is classified according to its location:

- supraglottis (false vocal cords)

- glottis (true vocal cords)

- subglottis (downward extension from the vocal cords [rare]).

With intrinsic laryngeal cancer, the dominant and earliest indication is hoarseness that persists longer than 3 weeks; with extrinsic cancer, it’s a lump in the throat or pain or burning in the throat when drinking citrus juice or hot liquid. Later signs and symptoms of metastasis include dysphagia, dyspnea, cough, enlarged cervical lymph nodes, and pain radiating to the ear.

Thursday, May 11, 2017

Hyperacute T Waves On ECG

(Click on the image to enlarge)

ECG Findings

• T-wave amplitude/QRS amplitude greater than 75%.

• T waves greater than 5 mV in the limb leads.

• T waves greater than 10 mV in the precordial leads.

• T waves have asymmetric appearance.

Clinical Pearls

1. Hyperacute T waves occur very early (within minutes) during myocardial injury and are transient.

2. The term “hyperacute T waves” is reserved for the early stages of myocardial infarction. “Prominent T waves” can also be seen with LVH, early repolarization, or with hyperkalemia.

ECG Findings

• T-wave amplitude/QRS amplitude greater than 75%.

• T waves greater than 5 mV in the limb leads.

• T waves greater than 10 mV in the precordial leads.

• T waves have asymmetric appearance.

Clinical Pearls

1. Hyperacute T waves occur very early (within minutes) during myocardial injury and are transient.

2. The term “hyperacute T waves” is reserved for the early stages of myocardial infarction. “Prominent T waves” can also be seen with LVH, early repolarization, or with hyperkalemia.

Introduction to Herpes zoster

Also called shingles, herpes zoster is an acute unilateral and segmental inflammation of the dorsal root ganglia caused by infection with the herpesvirus varicella-zoster, which also causes chickenpox.

This infection usually occurs in adults. It produces localized vesicular skin lesions confined to a dermatome and severe neuralgic pain in peripheral areas innervated by the nerves arising in the inflamed root ganglia.

The prognosis is good unless the infection spreads to the brain. Eventually, most patients recover completely, except for possible scarring and, in corneal damage, visual impairment. Occasionally, neuralgia may persist for months or years.

Herpes zoster is found primarily in adults, especially those older than age 50. It seldom recurs.

Pathophysiology

Herpes zoster results from reactivation of varicella virus that has lain dormant in the cerebral ganglia (extramedullary ganglia of the cranial nerves) or the ganglia of posterior nerve roots since a previous episode of chickenpox.

Exactly how or why this reactivation occurs isn’t clear. Some believe that the virus multiplies as it’s reactivated and that it’s neutralized by antibodies remaining from the initial infection. However, if effective antibodies aren’t present, the virus continues to multiply in the ganglia, destroy the host neuron, and spread down the sensory nerves to the skin.

Clinical features

Herpes zoster usually runs a typical course with classic signs and symptoms. Serious complications sometimes occur.

Herpes zoster is found primarily in adults, especially those older than age 50. It seldom recurs.

Pathophysiology

Herpes zoster results from reactivation of varicella virus that has lain dormant in the cerebral ganglia (extramedullary ganglia of the cranial nerves) or the ganglia of posterior nerve roots since a previous episode of chickenpox.

Exactly how or why this reactivation occurs isn’t clear. Some believe that the virus multiplies as it’s reactivated and that it’s neutralized by antibodies remaining from the initial infection. However, if effective antibodies aren’t present, the virus continues to multiply in the ganglia, destroy the host neuron, and spread down the sensory nerves to the skin.

Clinical features

Herpes zoster usually runs a typical course with classic signs and symptoms. Serious complications sometimes occur.

Onset of disease

Herpes zoster begins with fever and malaise. Within 2 to 4 days, severe deep pain, pruritus, and paresthesia or hyperesthesia develop, usually on the trunk and occasionally on the arms and legs in a dermatomal distribution. Pain may be continuous or intermittent and usually lasts from 1 to 4 weeks.

Herpes zoster begins with fever and malaise. Within 2 to 4 days, severe deep pain, pruritus, and paresthesia or hyperesthesia develop, usually on the trunk and occasionally on the arms and legs in a dermatomal distribution. Pain may be continuous or intermittent and usually lasts from 1 to 4 weeks.

Post-traumatic Pneumothorax.

A 24 years old male was brought to radiology department for X-ray chest following a road traffic accident. The X ray is shown below:

Radiological Findings: Chest X-ray shows presence of the air within the right pleural cavity with volume loss of right lung, as a result the right lung has partially collapsed. The outline of collapsed lung is seen well against the air.

Diagnosis: Post-traumatic Pneumothorax.

Clinical Discussion: Presence of the air within the pleural cavity is termed as the pneumothorax.

Air enters into the pleural cavity through the defect in pleural layers either spontaneously or due to trauma.

Radiological Findings: Chest X-ray shows presence of the air within the right pleural cavity with volume loss of right lung, as a result the right lung has partially collapsed. The outline of collapsed lung is seen well against the air.

Diagnosis: Post-traumatic Pneumothorax.

Clinical Discussion: Presence of the air within the pleural cavity is termed as the pneumothorax.

Air enters into the pleural cavity through the defect in pleural layers either spontaneously or due to trauma.

Wednesday, May 10, 2017

APlastic and Hypoplastic Anemias

These disorders generally produce fatal bleeding or infection, particularly when they’re idiopathic or stem from the use of chloramphenicol or from infectious hepatitis. Mortality for patients who have aplastic anemia with severe pancytopenia is 80% to 90%.

Causes

Aplastic anemias usually develop when damaged or destroyed stem cells inhibit red blood cell (RBC) production. Less commonly, they develop when damaged bone marrow microvasculature creates an unfavorable environment for cell growth and maturation. About half of such anemias result from drugs (antibiotics, anticonvulsants), toxic agents (such as benzene and chloramphenicol), or radiation. The rest may result from immunologic factors (unconfirmed), severe disease (especially hepatitis), or preleukemic and neoplastic infiltration of bone marrow.

Idiopathic anemias may be congenital and account for about 50% of all confirmed occurrences. Two such forms of aplastic anemia have been identified: congenital hypoplastic anemia (Blackfan-Diamond anemia), which develops between ages 2 months and 3 months, and Fanconi’s syndrome, which develops between birth and age 10.

With Fanconi’s syndrome, chromosomal abnormalities are typically associated with multiple congenital anomalies—such as dwarfism and hypoplasia of the kidneys and spleen. In the absence of a consistent familial or genetic history of aplastic anemia, researchers suspect that these congenital abnormalities result from an induced change in the development of the fetus.

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of aplastic anemias vary with the severity of pancytopenia but usually develop insidiously. These include progressive weakness and fatigue, shortness of breath, headache, pallor and, ultimately, tachycardia and heart failure. Thrombocytopenia leads to ecchymosis, petechiae, and hemorrhage, especially from the mucous membranes (nose, gums, rectum, and vagina) or into the retina or central nervous system. Neutropenia may lead to infection (with fever, oral and rectal ulcers, and sore throat) but without characteristic inflammation.

Ocular Herpes Simplex.

Ocular herpetic disease may be neonatal, primary, or recurrent.

Neonatal disease occurs secondary to passage through an infected birth canal, and is usually HSV type 2.

Primary ocular herpes may present as a blepharitis (grouped eyelid vesicles on an erythematous base), conjunctivitis, or keratoconjunctivitis.

Patients with keratoconjunctivitis commonly note pain, irritation, foreign body sensation, redness, photophobia, tearing, and occasionally decreased visual acuity. Follicles and preauricular adenopathy may be present. Initially, the keratitis is diffuse and punctate, but after 24 hours, fluorescein demonstrates either serpiginous ulcers or multiple diffuse epithelial defects. True dendritic ulcers are rarely seen in primary disease.

Ocular Herpes Simplex. This patient has a history of ocular herpes simplex since childhood. Grouped vesicles on an erythematous base with periorbital erythema are seen. Honey-colored crusts suggest secondary impetigo

Recurrent: Most ocular herpetic infections are manifestations of recurrent disease rather than a primary ocular infection.

These may be triggered by ultraviolet laser treatment, topical ocular medications (β-blockers, prostaglandins), and immunosuppression (especially ophthalmic topical glucocorticoids).

Recurrent disease most commonly presents as keratoconjunctivitis with a watery discharge, conjunctival injection, irritation, blurred vision, and preauricular lymph node involvement. Corneal involvement initially is punctate, but evolves into a dendritic keratitis. The linear branches classically end in bead-like extensions called terminal bulbs. Fluorescein dye demonstrates primarily the corneal defect; the terminal bulbs are best seen with rose stain. In addition to the dendritic pattern, fluorescein stain may instead take on a geographic or ameboid shape, secondary to widening of the

dendrite.

Neonatal disease occurs secondary to passage through an infected birth canal, and is usually HSV type 2.

Primary ocular herpes may present as a blepharitis (grouped eyelid vesicles on an erythematous base), conjunctivitis, or keratoconjunctivitis.

Patients with keratoconjunctivitis commonly note pain, irritation, foreign body sensation, redness, photophobia, tearing, and occasionally decreased visual acuity. Follicles and preauricular adenopathy may be present. Initially, the keratitis is diffuse and punctate, but after 24 hours, fluorescein demonstrates either serpiginous ulcers or multiple diffuse epithelial defects. True dendritic ulcers are rarely seen in primary disease.

Ocular Herpes Simplex. This patient has a history of ocular herpes simplex since childhood. Grouped vesicles on an erythematous base with periorbital erythema are seen. Honey-colored crusts suggest secondary impetigo

Recurrent: Most ocular herpetic infections are manifestations of recurrent disease rather than a primary ocular infection.

These may be triggered by ultraviolet laser treatment, topical ocular medications (β-blockers, prostaglandins), and immunosuppression (especially ophthalmic topical glucocorticoids).

Recurrent disease most commonly presents as keratoconjunctivitis with a watery discharge, conjunctival injection, irritation, blurred vision, and preauricular lymph node involvement. Corneal involvement initially is punctate, but evolves into a dendritic keratitis. The linear branches classically end in bead-like extensions called terminal bulbs. Fluorescein dye demonstrates primarily the corneal defect; the terminal bulbs are best seen with rose stain. In addition to the dendritic pattern, fluorescein stain may instead take on a geographic or ameboid shape, secondary to widening of the

dendrite.

Tuesday, May 9, 2017

Malignant Melanoma

Incidence of malignant melanoma, a neoplasm that arises from melanocytes, has increased by 50% in the past 20 years. In particular, an increase in incidence of melanoma in situ suggests earlier detection. The disorder varies in different populations but is about 10 times more common in white than in nonwhite populations.

The four types of melanomas are

- superficial spreading melanoma,

- nodular malignant melanoma,

- lentigo maligna melanoma, and

- acral-lentiginous melanoma.

Melanoma spreads through the lymphatic and vascular systems and metastasizes to the regional lymph nodes, skin, liver, lungs, and central nervous system (CNS). Its course is unpredictable, however, and recurrence and metastasis may occur more than 5 years after resection of the primary lesion. If it spreads to regional lymph nodes, the patient has a 50% chance of survival.

The prognosis varies with tumor thickness. Generally, superficial lesions are curable, whereas deeper lesions tend to metastasize. The Breslow Level Method measures tumor depth from the granular level of the epidermis to the deepest melanoma cell. Melanoma lesions less than 0.76 mm deep have an excellent prognosis, whereas deeper lesions (more than 0.76 mm deep) are at risk for metastasis. The prognosis is better for a tumor on an extremity (which is drained by one lymphatic network) than for one on the head, neck, or trunk (which is drained by several networks).

Causes & Risk Factors

Several factors may influence the development of melanoma:

Common sites for melanoma are on the head and neck in men, on the legs in women, and on the backs of people exposed to excessive sunlight. Up to 70% arise from a preexisting nevus. They rarely appear in the conjunctiva, choroid, pharynx, mouth, vagina, or anus.

The prognosis varies with tumor thickness. Generally, superficial lesions are curable, whereas deeper lesions tend to metastasize. The Breslow Level Method measures tumor depth from the granular level of the epidermis to the deepest melanoma cell. Melanoma lesions less than 0.76 mm deep have an excellent prognosis, whereas deeper lesions (more than 0.76 mm deep) are at risk for metastasis. The prognosis is better for a tumor on an extremity (which is drained by one lymphatic network) than for one on the head, neck, or trunk (which is drained by several networks).

Causes & Risk Factors

Several factors may influence the development of melanoma:

- Excessive exposure to ultraviolet light. Melanoma is most common in sunny, warm areas and commonly develops on parts of the body that are exposed to the sun. A person who has a blistering sunburn before age 20 has twice the risk of developing melanoma.

- Skin type. Most persons who develop melanoma have blond or red hair, fair skin, and blue eyes; are prone to sunburn; and are of Celtic or Scandinavian descent. Melanoma is rare among blacks; when it does develop, it usually arises in lightly pigmented areas (the palms, plantar surface of the feet, or mucous membranes).

- Autoimmune factors. Genetic and autoimmune effects may be causes.

- Hormonal factors. Pregnancy may increase risk and exacerbate growth.

- Family history. A person with a family history of melanoma has eight times the risk of developing the disorder.

- History of melanoma. A person who has had one melanoma has 10 times the risk of developing a second.

Common sites for melanoma are on the head and neck in men, on the legs in women, and on the backs of people exposed to excessive sunlight. Up to 70% arise from a preexisting nevus. They rarely appear in the conjunctiva, choroid, pharynx, mouth, vagina, or anus.

Sunday, May 7, 2017

Introduction to Mumps

Also known as infectious or epidemic parotitis, mumps is an acute viral disease caused by a paramyxovirus. It’s most prevalent in unvaccinated children between ages 2 and 12, but it can occur in other age-groups. Infants younger than age 1 seldom get this disease because of passive immunity from maternal antibodies. Peak incidence occurs during late winter and early spring.

The prognosis for complete recovery is good, although mumps sometimes causes complications.

Etiology

The mumps paramyxovirus is found in the saliva of an infected person and is transmitted by droplets or by direct contact. The virus is present in the saliva 6 days before to 9 days after onset of parotid gland swelling; the 48-hour period immediately preceding onset of swelling is probably the time of highest communicability.

The incubation period ranges from 14 to 25 days (the average is 18 days). One attack of mumps (even if unilateral) almost always confers lifelong immunity.

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of mumps vary widely. An estimated 30% of susceptible people have subclinical illness. Mumps usually begins with prodromal signs and symptoms that last for 24 hours; these include myalgia, anorexia, malaise, headache, and low-grade fever, followed by an earache that’s aggravated by chewing, parotid gland tenderness and swelling, a temperature of 101° to 104° F (38.3° to 40° C), and pain when chewing or when drinking sour or acidic liquids. Simultaneously with the swelling of the parotid gland or several days later, one or more of the other salivary glands may become swollen.

The incubation period ranges from 14 to 25 days (the average is 18 days). One attack of mumps (even if unilateral) almost always confers lifelong immunity.

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of mumps vary widely. An estimated 30% of susceptible people have subclinical illness. Mumps usually begins with prodromal signs and symptoms that last for 24 hours; these include myalgia, anorexia, malaise, headache, and low-grade fever, followed by an earache that’s aggravated by chewing, parotid gland tenderness and swelling, a temperature of 101° to 104° F (38.3° to 40° C), and pain when chewing or when drinking sour or acidic liquids. Simultaneously with the swelling of the parotid gland or several days later, one or more of the other salivary glands may become swollen.

Herpes Zoster Opthalmicus

A middle aged lady presented with a vesicular rash on her face that was seen to be involving the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve.

The case was diagnosed as Herpes Zoster Opthalmicus

Case Discussion:

Reactivation of endogenous latent varicella-zoster virus within the trigeminal ganglion with neuronal spread through the ophthalmic branch results in crops of grouped vesicles on the forehead and periocularly.

Clinical features; Patients typically present with periocular rash and an injected eye, along with a watery discharge. The most common corneal lesion is punctate epithelial keratitis, in which

the cornea has a ground-glass appearance because of stromal edema. Pseudodendrites, also very common, form from mucous deposition, are usually peripheral, and stain moderate to poorly with fluorescein. These may be differentiated from the dendrites of herpes simplex in that the pseudodendrites lack the rounded terminal bulbs at the end of the branches, and are broader and more plaquelike. Anterior stromal infiltrates may be seen in the second or third week after the acute

infection. Follicles (hyperplastic lymphoid tissue that appears as gray or white lobular elevations, particularly in the inferior cul-de-sac) and regional adenopathy may or may not be present. Iritis is seen in approximately 40% of patients.

The case was diagnosed as Herpes Zoster Opthalmicus

Case Discussion:

Reactivation of endogenous latent varicella-zoster virus within the trigeminal ganglion with neuronal spread through the ophthalmic branch results in crops of grouped vesicles on the forehead and periocularly.

Clinical features; Patients typically present with periocular rash and an injected eye, along with a watery discharge. The most common corneal lesion is punctate epithelial keratitis, in which

the cornea has a ground-glass appearance because of stromal edema. Pseudodendrites, also very common, form from mucous deposition, are usually peripheral, and stain moderate to poorly with fluorescein. These may be differentiated from the dendrites of herpes simplex in that the pseudodendrites lack the rounded terminal bulbs at the end of the branches, and are broader and more plaquelike. Anterior stromal infiltrates may be seen in the second or third week after the acute

infection. Follicles (hyperplastic lymphoid tissue that appears as gray or white lobular elevations, particularly in the inferior cul-de-sac) and regional adenopathy may or may not be present. Iritis is seen in approximately 40% of patients.

Pleural Calcification On Chest X ray

A 45 years male patient came to radiology department for X-ray chest with history of cough and expectoration of several months duration.

The X ray is shown below:

Chest X-ray (in the above picture) shows a large plaque of calcification covering the lateral and anterior part of left lung. There is crowding of overlying ribs.

Calcified pleural plaques have a characteristic rolled edge along its margin

Left upper lobe shows fibrotic lesions with bronchiectatic change and calcific spots are also seen.

Explanation:

Magnified view (shown below) shows that pleural calcification plaques have a characteristic rolled edge along its margin. (marked by arrows)

In general, pleural calcification is sequelae of hemothorax, empyema, tuberculosis or asbestos exposure.

The X ray is shown below:

Chest X-ray (in the above picture) shows a large plaque of calcification covering the lateral and anterior part of left lung. There is crowding of overlying ribs.

Calcified pleural plaques have a characteristic rolled edge along its margin

Left upper lobe shows fibrotic lesions with bronchiectatic change and calcific spots are also seen.

Explanation:

Magnified view (shown below) shows that pleural calcification plaques have a characteristic rolled edge along its margin. (marked by arrows)

In general, pleural calcification is sequelae of hemothorax, empyema, tuberculosis or asbestos exposure.

Saturday, May 6, 2017

Introduction to Dermatophytosis

Also called tinea or ringworm, dermatophytosis is a disease that can affect the scalp (tinea capitis), body (tinea corporis), nails (tinea unguium), feet (tinea pedis), groin (tinea cruris), and bearded skin (tinea barbae).

Tinea infections are quite prevalent in the United States and are usually more common in males than in females. With effective treatment, the cure rate is very high, although about 20% of persons with infected feet or nails develop chronic conditions.

Causes

Tinea infections (except for tinea versicolor) result from dermatophytes (noncandidal fungi) of the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton that involve the stratum corneum, nails or hair.

Transmission can occur directly (through contact with infected lesions) or indirectly (through contact with contaminated articles, such as shoes, towels, or shower stalls). Some cases come from animals or soil.

Signs and symptoms

Lesions vary in appearance and duration with the type of infection:

Tinea infections are quite prevalent in the United States and are usually more common in males than in females. With effective treatment, the cure rate is very high, although about 20% of persons with infected feet or nails develop chronic conditions.

Causes

Tinea infections (except for tinea versicolor) result from dermatophytes (noncandidal fungi) of the genera Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton that involve the stratum corneum, nails or hair.

Transmission can occur directly (through contact with infected lesions) or indirectly (through contact with contaminated articles, such as shoes, towels, or shower stalls). Some cases come from animals or soil.

Signs and symptoms

Lesions vary in appearance and duration with the type of infection:

Tinea capitis, which mainly affects children, is characterized by round erythematous patches on the scalp, causing hair loss with scaling. In some children, a hypersensitivity reaction develops, leading to boggy, inflamed, commonly pus-filled lesions (kerions).

Tinea corporis produces flat lesions on the skin at any site except the scalp, bearded skin, groin, palms, or soles. These lesions may be dry and scaly or moist and crusty; as they enlarge, their centers heal, causing the classic ring-shaped appearance.

Tinea unguium (onychomycosis) infection typically starts at the tip of one or more toenails (fingernail infection is less common) and produces gradual thickening, discoloration, and crumbling of the nail, with accumulation of subungual debris. Eventually, the nail may be destroyed completely.

Tinea pedis causes scaling and blisters between the toes. Severe infection may result in inflammation, with severe itching and pain on walking. A dry, squamous inflammation may affect the entire sole.

Anisocoria

Anisocoria is a disparity of pupil size.

To determine the abnormal pupil, compare pupil sizes in light and dark. It is accentuated in the paretic muscle. If the iris sphincter (or its innervation) is involved, the anisocoria will be increased in bright light. If the iris dilator muscle (or its innervation) is affected, it will be more

pronounced in darkness.

Up to 20% of normal individuals have physiologic anisocoria of 1 to 2 mm.

Other causes of anisocoria with an abnormally large pupil include

- mydriatic drops,

- contamination from a scopolamine patch,

- an Adie pupil, and

- ocular trauma with iris sphincter damage.

Post traumatic Anisocoria. Marked chronic anisocoria secondary to prior trauma as a child

A dilated pupil due to anticholinergic agents (eg, atropine) does not react to light, although a dilated pupil due to sympathomimetics still has some response.

An abnormally small pupil may be secondary to Horner syndrome, chronic Adie pupil (8 weeks or more after the event), iritis, and eye drops (pilocarpine).

Miosis secondary to pupillary sphincter muscle spasm may be transiently observed after ocular trauma, followed by mydriasis.

To determine the abnormal pupil, compare pupil sizes in light and dark. It is accentuated in the paretic muscle. If the iris sphincter (or its innervation) is involved, the anisocoria will be increased in bright light. If the iris dilator muscle (or its innervation) is affected, it will be more

pronounced in darkness.

Up to 20% of normal individuals have physiologic anisocoria of 1 to 2 mm.

Other causes of anisocoria with an abnormally large pupil include

- mydriatic drops,

- contamination from a scopolamine patch,

- an Adie pupil, and

- ocular trauma with iris sphincter damage.

Post traumatic Anisocoria. Marked chronic anisocoria secondary to prior trauma as a child

A dilated pupil due to anticholinergic agents (eg, atropine) does not react to light, although a dilated pupil due to sympathomimetics still has some response.

An abnormally small pupil may be secondary to Horner syndrome, chronic Adie pupil (8 weeks or more after the event), iritis, and eye drops (pilocarpine).

Miosis secondary to pupillary sphincter muscle spasm may be transiently observed after ocular trauma, followed by mydriasis.

Thursday, May 4, 2017

Left Main Coronary Artery Lesion - ECG

ECG Findings

• ST segment elevation in the precordial leads (V2-V6) and high lateral leads (I, aVL).

• Reciprocal ST segment depressions in the inferior leads (II, III, aVF).

• ST segment elevation in AVR coupled with reciprocal ST depressions may indicate AMI from left main disease.

Significant ST elevation is present in the precordial leads (V2-V6) and high lateral leads (I and aVL) (arrows). In this example, significant Q waves have appeared, signaling infarction (arrowhead).

Clinical Pearls

1. The left main coronary artery branches into the left anterior descending artery and the circumflex artery.It supplies blood to the ventricular septum and the anterior and lateral aspects of the left ventricle, usually sparing the posterior and inferior portion, which is most often served by the right coronary artery.

Wednesday, May 3, 2017

Corrosive Esophagitis

A 50 year old woman was seen in emergency after ingesting a chemical substance . Esophagogastrodudenoscopy was performed and the picture is shown below.

Corrosive Esophagitis Case Discussion

Introduction

Initial esophagoscopy. (A) Middle esophagus shows whitish discoloration. (B) Distal esophagus shows exudates with easy touch bleeding.

The case was diagnosed as Corrosive Esophagitis

Corrosive Esophagitis Case Discussion

Introduction

Inflammation and damage to the esophagus after ingestion of a caustic chemical is called corrosive or caustic esophagitis. Similar to a burn, this injury may be temporary or lead to permanent stricture (narrowing or stenosis) of the esophagus that requires corrective surgery.

Severe injury can quickly lead to esophageal perforation, mediastinitis, and death from infection, shock, and massive hemorrhage (due to aortic perforation).

Severe injury can quickly lead to esophageal perforation, mediastinitis, and death from infection, shock, and massive hemorrhage (due to aortic perforation).

Causes

The most common chemical injury to the esophagus follows the ingestion of lye or other strong alkalies; less commonly, injury follows the ingestion of strong acids. The type and amount of chemical ingested determine the severity and location of the damage.

In children, household chemical ingestion is accidental; in adults, it’s usually a suicide attempt or gesture. The chemical may damage only the mucosa or submucosa, or it may damage all layers of the esophagus.

The most common chemical injury to the esophagus follows the ingestion of lye or other strong alkalies; less commonly, injury follows the ingestion of strong acids. The type and amount of chemical ingested determine the severity and location of the damage.

In children, household chemical ingestion is accidental; in adults, it’s usually a suicide attempt or gesture. The chemical may damage only the mucosa or submucosa, or it may damage all layers of the esophagus.

Pathology

Esophageal tissue damage occurs in three phases:

- in the acute phase, edema and inflammation;

- in the latent phase, ulceration, exudation, and tissue sloughing; and

- in the chronic phase, diffuse scarring.

Tuesday, May 2, 2017

Brief Summary of Otosclerosis

Incidence: It occurs in at least 10% of the population in the United States. It commonly affects both ears and is seen in many females between the ages of 15 and 30.

Causes

Otosclerosis appears to result from a genetic factor transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait; many patients report family histories of hearing loss (excluding presbycusis). Pregnancy may trigger the onset of this condition.

Otosclerosis appears to result from a genetic factor transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait; many patients report family histories of hearing loss (excluding presbycusis). Pregnancy may trigger the onset of this condition.

Signs and symptoms

Spongy bone in the otic capsule immobilizes the footplate of the normally mobile stapes, disrupting the conduction of vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the cochlea. This causes progressive unilateral hearing loss, which may advance to bilateral deafness. Other symptoms include tinnitus and paracusis of Willis (hearing conversation better in a noisy environment than in a quiet one).

Spongy bone in the otic capsule immobilizes the footplate of the normally mobile stapes, disrupting the conduction of vibrations from the tympanic membrane to the cochlea. This causes progressive unilateral hearing loss, which may advance to bilateral deafness. Other symptoms include tinnitus and paracusis of Willis (hearing conversation better in a noisy environment than in a quiet one).

Monday, May 1, 2017

Pleuropulmonary Tuberculosis - Chest X-Ray

A 45 years old male came to radiology department for X-ray chest with history of cough, mild fever and weight loss. The x ray is shown below:

X-ray chest shows fibro infiltrative lesions in right upper zone with areas of early calcification and moderate pleural effusion on left sidewith minimal tracheal pull to right side.

Comments And Explanation: Pleural effusion is the accumulation of fluid in the pleural space, i.e.

between the visceral and parietal layers of pleura. The fluid may be transude, exudate, blood, chyle or rarely bile.

Pleural fluid casts a shadow of the density of water on the chest radiograph. The most dependent recess of the pleura is the posterior costophrenic angle. A small effusion will, therefore, tend to collect posteriorly, however, a lateral decubitus view is the most sensitive film to detect small quantity of free pleural effusion (as small as 50 ml). 100–200 ml of pleural fluid is required to be seen above the dome of the diaphragm on frontal chest radiograph. As more fluid is accumulated, a

homogeneous opacity spreads upwards, obscuring the lung base.

Typically this opacity has a fairly well-defined, concave upper edge (as seen in picture above), which

is higher laterally and obscures the diaphragmatic shadow. Frequently the fluid will track into the pleural fissures.

A massive effusion may cause complete radiopacity of a hemithorax. The underlying lung will retract

towards its hilum, and the space occupying effect of the effusion will push the mediastinum towards the opposite side.

USG chest confirms the presence or absence of the pleural fluid; it also shows the septations within the pleural fluid with or without solid component within the lesion. USG helps in guiding aspiration of pleural fluid.

CT scan is the most sensitive modality for detection of presence of minimal fluid. It allows distinction between free and loculated fluid showing its extent and localization.

X-ray chest shows fibro infiltrative lesions in right upper zone with areas of early calcification and moderate pleural effusion on left sidewith minimal tracheal pull to right side.

Comments And Explanation: Pleural effusion is the accumulation of fluid in the pleural space, i.e.

between the visceral and parietal layers of pleura. The fluid may be transude, exudate, blood, chyle or rarely bile.

Pleural fluid casts a shadow of the density of water on the chest radiograph. The most dependent recess of the pleura is the posterior costophrenic angle. A small effusion will, therefore, tend to collect posteriorly, however, a lateral decubitus view is the most sensitive film to detect small quantity of free pleural effusion (as small as 50 ml). 100–200 ml of pleural fluid is required to be seen above the dome of the diaphragm on frontal chest radiograph. As more fluid is accumulated, a

homogeneous opacity spreads upwards, obscuring the lung base.

Typically this opacity has a fairly well-defined, concave upper edge (as seen in picture above), which

is higher laterally and obscures the diaphragmatic shadow. Frequently the fluid will track into the pleural fissures.

A massive effusion may cause complete radiopacity of a hemithorax. The underlying lung will retract

towards its hilum, and the space occupying effect of the effusion will push the mediastinum towards the opposite side.

USG chest confirms the presence or absence of the pleural fluid; it also shows the septations within the pleural fluid with or without solid component within the lesion. USG helps in guiding aspiration of pleural fluid.

CT scan is the most sensitive modality for detection of presence of minimal fluid. It allows distinction between free and loculated fluid showing its extent and localization.

Anterior Uveitis (Iritis)

Introduction: The uvea is the middle layer of the eye. Its anterior portion includes the iris and ciliary body; the posterior portion includes the choroid. Inflammation of the anterior portion is called anterior uveitis or iritis.

Etiology: It is often idiopathic, but approximately half of cases are associated with systemic

disease. These include :

Clinical features include conjunctival hyperemia, hyperemic perilimbal vessels (“ciliary flush”), miosis, decreased visual acuity, photophobia, tearing, and pain.

Anterior Uveitis. Marked conjunctival injection and perilimbal hyperemia (“ciliary flush”) are seen in this patient with recurrent iritis

The slit-lamp may demonstrate a hypopyon, cells, flare, and keratic precipitates.

Keratic precipitates are agglutinated inflammatory cells adherent to the posterior corneal endothelium. These precipitates appear either as fine gray-white deposits or as a large, flat, greasy-looking area (“mutton fat”).

The IOP may be decreased due to decreased aqueous production by the inflamed ciliary body, or increased secondary to inflammatory debris within the trabeculae of the anterior chamber angle obstructing outflow.

Etiology: It is often idiopathic, but approximately half of cases are associated with systemic

disease. These include :

- Inflammatory disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, Behçet disease, sarcoid),

- HLA-B27-associated conditions (ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, Reiter syndrome), and

- Infectious causes (zoster, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, AIDS).

Clinical features include conjunctival hyperemia, hyperemic perilimbal vessels (“ciliary flush”), miosis, decreased visual acuity, photophobia, tearing, and pain.

Anterior Uveitis. Marked conjunctival injection and perilimbal hyperemia (“ciliary flush”) are seen in this patient with recurrent iritis

The slit-lamp may demonstrate a hypopyon, cells, flare, and keratic precipitates.

Keratic precipitates are agglutinated inflammatory cells adherent to the posterior corneal endothelium. These precipitates appear either as fine gray-white deposits or as a large, flat, greasy-looking area (“mutton fat”).

The IOP may be decreased due to decreased aqueous production by the inflamed ciliary body, or increased secondary to inflammatory debris within the trabeculae of the anterior chamber angle obstructing outflow.

Introduction to Diabetic Foot

A diabetic foot is a foot that exhibits any pathology that results directly from diabetes mellitus or any long-term (or “chronic”) complications of diabetes mellitus. Presence of several characteristic diabetic foot pathologies is called diabetic foot syndrome.

Infections in patients with diabetes are difficult to treat because these individuals have impaired microvascular circulation, which limits the access of phagocytic cells to the infected area and results in a poor concentration of antibiotics in the infected tissues.

Etiology

Diabetes mellitus is a disorder that primarily affects the microvascular circulation. In the extremities, microvascular disease due to “sugar-coated capillaries” limits the blood supply to the superficial and deep structures. Pressure due to ill-fitting shoes or trauma further compromises the local blood supply at the microvascular level, predisposing the patient to infection, which may involve the skin, soft tissues, bone, or all of these combined.

Diabetes also accelerates macrovascular disease, which is evident clinically as accelerating atherosclerosis and/or peripheral vascular disease. Most diabetic foot infections occur in the setting of good dorsalis pedis pulses; this finding indicates that the primary problem in diabetic foot infections is microvascular compromise.

Risk factors

Two main risk factors that cause diabetic foot ulcer are Diabetic Neuropathy and micro as well as macro ischemia. Diabetic patients often suffer from diabetic neuropathy due to several metabolic and neurovascular factors. Type of neuropathy called peripheral neuropathy causes loss of pain or feeling in the toes, feet, legs and arms due to distal nerve damage and low blood flow. Blisters and sores appear on numb areas of the feet and legs such as metatarso-phalangeal joints, heel region and as a result pressure or injury goes unnoticed and eventually become portal of entry for bacteria and infection.

Microbial Organisms involved in Infection

The microbiologic features of diabetic foot infections vary according to the tissue infected. In patients with diabetes, superficial skin infections, such as cellulitis, are caused by the same organisms as those in healthy hosts, namely group A streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus.

Deep soft-tissue infections in diabetic persons can be associated with gas-producing, gram-negative bacilli.